Reading & Questions / Gap Fill

Sonido

Mind yours languages

Where do words like 'bling' and 'nang' come from? A new documentary examines how youth culture sticks its tongue out at the Queen's English

Miranda Sawyer

Sunday August 14, 2005

The Observer

About halfway through next Wednesday's BBC Radio 1 Xtra documentary, Slangtionary, which attempts to explain where certain common urban phrases come from, an American rapper is asked what he thinks various British words mean. Sweetly, he gets almost all of them wrong. Which may make some older listeners feel better.

'Endz', 'blud', 'nang', 'butters' ... any idea? They're all everyday parlance for many UK teenagers, yet unlikely to be found in a lexicon, not even The Oxford Dictionary of Slang (try www.urbandictionary.com instead). Along with the distorted use of words like standard, bare and decent, such colloquialisms skid off the tongue of British urban youth, defining the speaker and the listener, alienating, explaining and classifying all at once. You don't get it? That's the point of slang.

Slangtionary acknowledges this and refuses to explain everything. There's an assumption that the listener will know what 'izzle' is (it's a way of speaking popularised by Snoop Dogg that turns most words into ones ending with izzle), that there's no need to clarify 'endz' (where you live) or 'nang' (cool). Even if you don't understand everything, you can still enjoy the show; trying to guess what they're talking about is part of the fun.

Elizabeth Biddlecombe, who produced Slangtionary, was inspired to do so when she moved from the UK to the west coast of the USA . 'I was surprised that people didn't always understand me,' she confesses. 'And when I started going out with an American boy, I found that if we were drunk or tired, then problems would occur. We'd both be going "what?" all the time.' Such lost-in-translation misunderstanding ran parallel with a shared transatlantic hip hop speak ('We both said "off the hook" or "it's all good"') and inspired Biddlecombe to investigate further.

Her documentary, which traces many current rap phrases to Oakland and the Bay area of California, and then nips back home to Britain to talk to academics, artists and teenagers, points up how most popular teenage slang comes from black speech and has done since the reggae explosion of the Seventies. Mistah FAB, a rapper from the Bay area, calls the way he and his friends speak 'nig-latin' (from pig-latin, a phrase which raised are in both the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People and the Ku Klux Klan).

These days, hip hop is an international language - think how quickly 'bling' and 'shorty' became part of British vocabulary - though British youth isn't just influenced by Afro-American rap. Afro-Caribbean chat and African ways of speech are also wound about in there, says Roots Manuva, born and bred in Stockwell, south London . Biddlecombe explains the dominance of hip hop speak as partly caused by record industry marketing and partly by the internet (teenagers will explain phrases to their instant messaging friends in other countries). 'On the one hand,' she says, 'slang is pinned to your physical location. And on the other, it's your tribe location, which is international and independent. So you'll have kids in Birmingham or Japan speaking izzle.'

Slangtionary is part of BBC Radio's Voices week, which runs from August 20 to 28, and celebrates the way we speak in the UK today. For Voices, more than 300 interviews were conducted with differently dialected sets of people, from the Channel Islands to the Shetland Isles. They were all asked the same 40 questions (to hear the results, tune into Word 4 Word on Wednesdays at 9am on Radio 4). Simon Elmes, creative director for BBC Radio, says that the research showed that we nurse two myths about the way we speak. One is that 'only we say that' - 'you wouldn't believe how many people said that "knackered" was a local word' - and the other is that 'no one says that any more'.

He agrees that, today, slang explodes and dies more quickly than before, due to mass communication - TV, mobiles, internet - and the fact that we move about more. As late as the early Eighties, more than 60 per cent of the UK population had never lived more than a dozen miles from where they were born: this no longer holds. Another recent development is that we're all anxious not to appear too posh; even upper-class people speak less correctly than 30 years ago. Weirdly, the middle and working classes used to have broader accents; now there's a linguistic levelling that's taking place across the country.

Professor Jean Aitchison, Emeritus professor of language and communication at Oxford University , agrees with Elmes about such levelling, but looks at slang slightly differently. 'Some of the changes in the way we speak aren't due to social implications, but to the properties of spoken sound,' she says. 'What is known as estuary English is having an impact on the whole of the UK , in Glasgow and in Manchester as well as around London .' She explains that, as a nation, we're losing the ends of our words, especially the ones that end with 't': 'It's natural, it's the way that sounds go.' In fact, poor old 't' is disappearing even in the middle of words - e.g. 'butters'is commonly said as 'bu'ers'. The most stable letters are 'm' and 'n', if you're interested; they're very unlikely to disappear from spoken language.

She also points out that our vowels are changing, so we're beginning to pronounce 'mean' as 'main', 'main' as 'mine' and 'mine' like 'main' - 'Our vowels are chasing each other'. This shift isn't unusual; it occurred in Shakespearean times, and you can hear it in the way New Zealanders speak. To a UK ear, Kiwis pronounce their 'i's as 'u's - 'fush and chups'.

Professor Aitchison's husband, John Ayto, is the editor of The Oxford University Dictionary of Slang. Recent additions include chav, bootilicious, bling, blog, dogging and lunchbox: 'I'm aware that once a slang word is in the dictionary,...'; people have already moved on. We struggle to keep up.' Still, there's always ye olde slange: 'gob' has been with us for five centuries and 'arse' was an everyday term 1,000 years ago.

Would you say arse to your granny? 'Personally, I don't find it offensive,' says Professor Aitchison. 'Not unless it's inappropriate. If a shop assistant swore at me, I'd walk out. But when I'm at Hackney market, it would be stupid to flinch every time someone used the f word.' 'You need to be able to switch from slang to something more formal,' agrees Slangtionary's Biddlecombe. 'Or you'll be at a severe disadvantage in life.'

Which explains the final truth about slang. Your mother will try and stop you speaking it. 'Oh yes, that's true across all generations,' says Elmes. 'People's mums try and change their accents. They want their children to speak properly.' S'standard, innit?

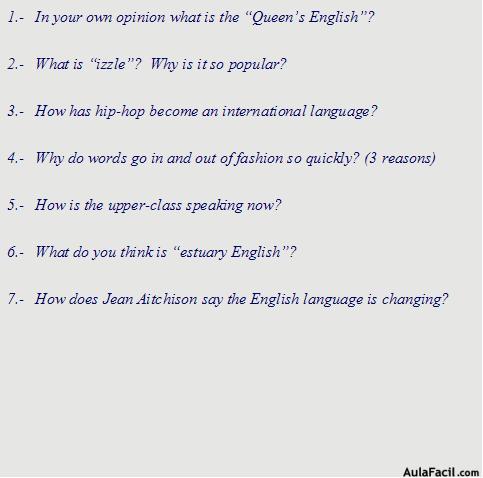

Comprehension Questions

A. True or False (Please correct the False statements)

| 1) | Nowadays teenagers only speak slang | |

| 2) | The show Slantionary goes into detail about the origin of all the news slang words | |

| 3) | England ans America use different slang | |

| 4) | British slang derives from many different places | |

| 5) | The pronunciation of the consonants is changing | |

Corregir

Ver Solución

Limpiar | ||

B. Answer the following questions according to the text

(Para ver las soluciones haga doble click en el área sombreada; un click vuelve a posición original)

C. Explain the meaning of the phrases bellow

| 1) | Sticks its tongue out at | |

| 2) | Skid off the tongue | |

| 3) | Transatlantic hip hop speak | |

| 4) | Slang is pinned to | |

| 5) | Such levelling | |

| 6) | It would be stupid to flinch | |

Corregir

Ver Solución

Limpiar | ||

D. In about 100 words summarise what is said in the text about the changes in the English language

Gap Fill

A. Complete each sentence with one of the words given.

Hinder / Behove / Diddle / Giggle / Enrapture / Indent / Apolitical / Knotty /Litigate / Mourn / Ordeal / Parable / Resilient / Shamble / Nondescript

| 1) | The purpose of the watchdog was to be totally . | |

| 2) | It us to reflection this matter. | |

| 3) | John felt that the shopkeeper was trying to him out of some money. | |

| 4) | He was totally with the girl on the floor below. | |

| 5) | In an attempt to their escape, the guards had locked the door. | |

| 6) | The first sentence of each paragraph was . | |

| 7) | I face the problem of what to have for breakfast. | |

| 8) | To means to institute legal proceedings against someone. | |

| 9) | The woman her husbands death for 7 months. | |

| 10) | The report on the event was every | |

| 11) | Julie had to write down every detail of her | |

| 12) | The of the prodigal son was one of her favourite stories. | |

| 13) | All computer system at Symantec must be highly . | |

| 14) | The night turned out to be a complete when it started to rain, we missed the train and Karen had to taken to hospital. | |

| 15) | The two children could not help but at their teacher´s new haircut. | |

Corregir

Ver Solución

Limpiar | ||